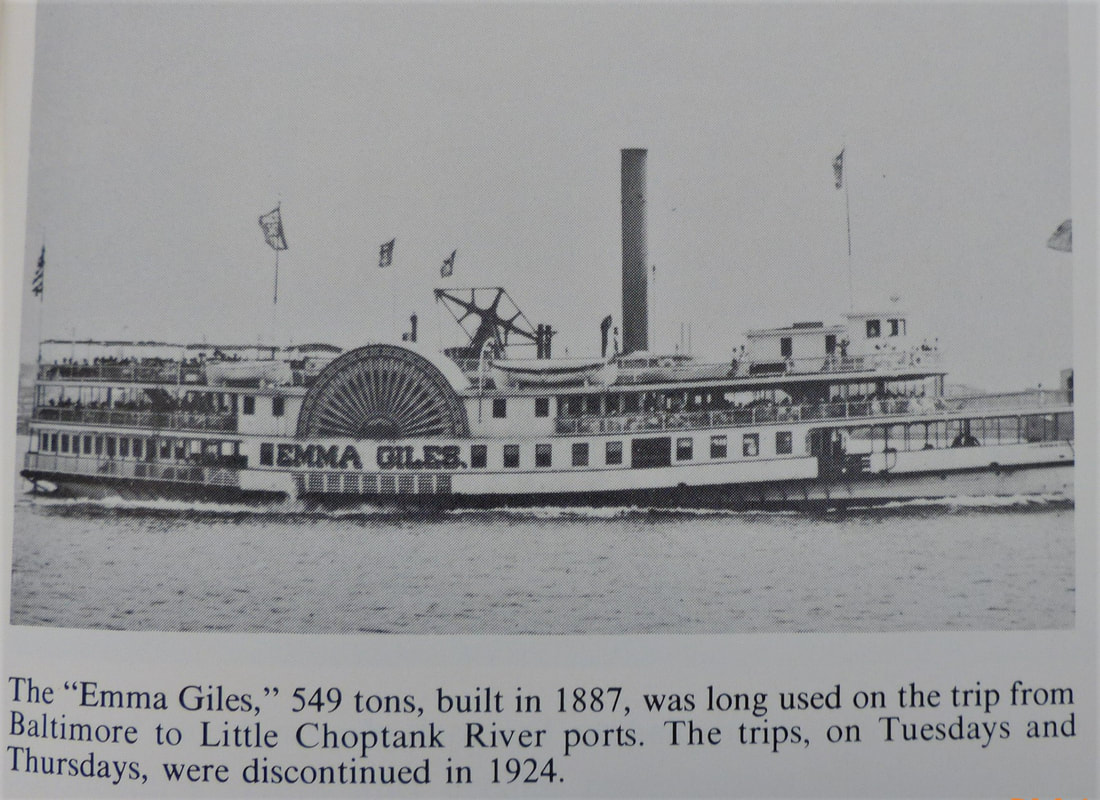

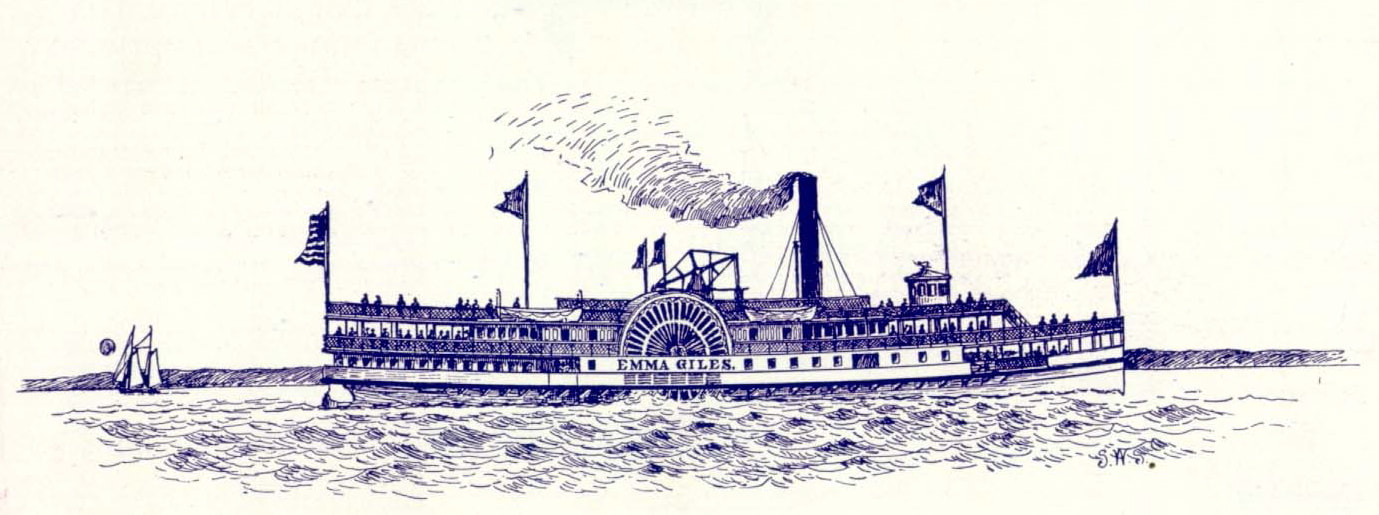

The above image is the sidewheel steamboat "Emma Giles" that would visit Taylors Island twice each week in the early days of the 20th century (see the recollections of Aunt Hester below). She was built in 1887 and had a capacity of 1,500 passengers. On New Years Day 1924, the Emma Giles collided with the SS Steel Trader in heavy fog near to Taylors Island and the Little Choptank River. She sustained damage to her starboard side, including her paddle wheel. Luckily none of the passengers were injured.

“TAYLORS ISLAND AS IT ONCE WAS”

As I get older, it becomes apparent to me that I grew up in a time and place that only a few living today remember. My grandchildren have no knowledge of life without paved roads, television, refrigerators with freezers, a school bus that comes right to your door, electricity, cell phones, and on and on. I considered writing about my experiences growing up on Taylors Island. But I recently came across some letters that my Aunt Hester A. Neild wrote to my mother, Mabel Neild in the 1960’s.

Some of you will remember my “Aunt Hester”. She was teacher and principal at East Cambridge School for more than 50 years, finally retiring only because she had to at the age of seventy. She loved to read, tend her flower garden, and write letters. She was born in 1902 and lived on the Island directly across from the general store. Some of her letters are real history lessons. Those about Taylors Island are treasures to be enjoyed, and that is why I offer them for your enjoyment. These are her words.

“Sometimes my thoughts go back to the early days at Taylors Island, and in my mind I can still look across the road from my house and see the old Chapel of Ease, and horses lined up there for shoeing, and I may walk on past the Chapel to the Slaughter Creek shore to the small wooden building where old Charlie Balderston – a genial Negro – sold a quart of shucked oysters for about $.15. I remember the Old Chapel being used, at other times, for Church Suppers, Strawberry Festivals, or Socials for the Island churches. Now it has been restored and moved to the grounds of the Grace Episcopal Church, where I was organist for 15 years during my early days of teaching. When the Old Chapel was used as a blacksmith shop, Mr. Bill Dashiell kept the forge hot and ready for shoeing the horses, and for repairing the iron accessories for boats and farm implements.

“Another memory so clear is that of the sprawling old tomato cannery not far from Slaughter Creek. In the summer and fall, there was always a tangy smell in the air from the cooking tomatoes, and there were long lines of trucks and horse-drawn wagons loaded with tomatoes, waiting to be unloaded. They were unloaded for weighing, scalding, skinning, canning, labeling, and then the filled cans were loaded for hauling away on the Old Emma Giles steamboat, which came to the Island twice each week. Later, after the new “State Road” was built to the Island, hauling was by truck. From our house, we could hear the talking and singing of the Colored workers above the clatter and hissing of the machinery and the steam used for scalding. It was quite an adventure to walk through that busy hive of industry, and be warned “don’t come too near the hot furnace, or belts driving the machinery, or the conveyors carrying the buckets of tomatoes and cans”. It does not seem possible that all this has vanished and exists only in our memories.

“Close to the cannery and on the same side of the road, I recall that there was a long, gray, wooden country store. It bordered on the Island’s oyster shell road. If one approached the store from the cannery, the rear of the store was reached first. You might walk over the “stile” (up two steps – over – down two steps) and reach the path leading to the front porch of the store. Or, if you wanted to walk further and go past the broad back of the store to the big gate used by the wagons, one could then go into the side door of the giant warehouse called the “grocery”, or onto the front porch of the store. This path took you by a narrow building that was a “carpenter shop”, used by the local undertaker, Mr. Henry Lambdin, to build and store coffins. It was fun to go through the gloomy interior of the “grocery”, so full of all kinds of things for the store. Then into the fascinatingly cluttered “store” with its long, long counters, its bins of flour, chicken feed, hog feed, horse feed, etc., and the gleaming glass showcase with its assortment of penny candy. There were horehound drops, stick candy encircled with gaudy rings, little tin pans of white candy with a blob of yellow to make it appear like a “fried egg”, and rainbow coconut ribbons. It is nice to recall the chocolate “Penny Pigs” that sometimes had a real penny inside. For the sake of finding that hidden penny, we sometimes spent several pennies. And I like to remember the Prize Boxes for a nickel, and the glass showcases of ribbons, and the counters loaded with bolts of cloth to be bought by the yard, or half-yard, and the horse blankets, and horse collars, and harness, and stationary. Then there were barrels of peanuts in the shell, a showcase with cigars, pipe tobacco, and chewing tobacco. It always seemed the people who bought the old “plug tobacco” were getting a special treat. There were oblong blocks of the brown “delicacy” and the men would get a generous slice for a nickel, then quickly begin chewing it with delight. It really was a wonderful place, and I know we were all sad in 1916 when that old store was destroyed by fire.

“It was sometime around 1916 or 1917 as I was going to school on the Island, and it seems to me that Mr. A. L. Stevenson was the teacher. I remember that we all left the school grounds and hurried down toward the “big blaze”, with our teacher cautioning us not to go too close. It seems they were experimenting in the store with “gasoline lights” in hopes that they could replace the old “coal oil” lamps.

“When using my shiny new refrigerator that makes ice cubes with such little effort, I often think of the “dairy houses” on stilts that were in every yard on the Island. Inside the cool little enclosures, there could be found a delicious homemade pie or cake, or “hogshead cheese”, or cornstarch pudding, or eggs laid by the family’s hens. The folks on the Island all had their own cows and plenty of milk. Plainly, in my mind’s eye, I see the cheesecloth bags of “clabbered milk” hung on nails or hooks and draining beside the little house to make “smearcase”. The making of “smearcase”, now known as cottage cheese, was an everyday chore and an easy one. We ate the delicious “smearcase” covered with sugar, or molasses, or preserves, or just plain. No canned fruit has ever tasted as wonderful to me as the peaches, pears, cherries and apples it was just customary to prepare and “can” in those days. Never have I been fortunate enough to find or make a “molasses” pie as good as my mother made with black molasses bought from a barrel at the country store and topped with slices of lemon.

“By fishing, crabbing, oystering, farming, building, and processing, the people of the Island were always sturdily self-sufficient in those days before the “State Road” was built in 1916. It took a long time to go to Cambridge over the old oyster shell roads. I remember how, when my father served on the jury, he often stayed overnight with his sister’s family at Church Creek rather than drive the long miles through the dark “big woods” and over the desolate road from Madison to the Island after dark. That sister was Mrs. William Willis. If my father planned to return home that night, I sometimes went with him as far as Church Creek, and stayed to play all day with my cousin Eleanor. As a child I thought “How I will enjoy driving a horse when I grow up!” But at 16, I had an automobile operator’s license and could drive the car my father had bought when the new road was built to the Island. We mainly used the car for the 16-mile trip to Cambridge, and no longer had to use the horses and carriage for that trip. I never derived the pleasure from driving a car that I anticipated I would have had driving our horses “George”, “Maude”, and “Bess”. The barn where the horses stayed was a place of pleasure. It held the horses and cows, wagon, carriages, the surrey, corn and hay.

“Then there were the pig pens we had for raising hogs to be slaughtered for food in the fall. Meat was processed into hams, spareribs, lard, sausage, liver pudding, and scrapple. The fat was cut into small cubes and cooked to make the lard and “cracklings”. Corn bread made with cracklings was a delicacy. Of all the things I loved about Island life, I wanted nothing to do with the killing of the hogs. The squealing of the doomed “sources of food” was nerve-wracking, and my mother would suggest that I “go play the organ as loud as you can to drown out the horrible noise”. “Slaughter Creek” is the body of water that separates Taylors Island from the mainland. My mother use to tell me it was named that because folks drove their beef cattle to the creek to slaughter them. The outgoing tides would then take away most of the unwanted results of the slaughter.

“I remember other diversions we had on the Island. I doubt that present day children get any more satisfaction from their many modern recreations than we did from setting our rabbit traps (called rabbit gums, in those days), and going through the thickets of blackberry and huckleberry bushes, and through close growing cedar and pine trees to see if our trap was “sprung”. It was exciting, and there was a sense of satisfaction when my brother (J. Stapleforte Neild) said, “We’ve caught one!” I suppose I have never admired the courage of anyone more than his courage when he raised the trap door and, somehow, managed to grasp that squirming rabbit by its hind feet. Then we would go back through the woods and up the lane to the house to receive the praise of our mother. We knew the rabbit would be a delicious supper the next day.

“Besides catching rabbits, the neighborhood children would fish, crab, find turtles and watercress, gather eggs, and many other fun things, and those things gave us a sense of adequacy and satisfaction. The fact that our parents were always home in the evenings to help with our homework and direct activities gave us a feeling of security that was real and deep. There was never a need for a psychologist or psychiatrist that I can recall. And we did not suffer poor education. I remember how my mother drilled me in the “multiplication tables” and in “spelling”. We were never exposed to “phonetics” during our entire school life, and yet, spelling and reading seemed very easy. We had “spelling bees” in school every day and got to be good spellers. At the end of my fifth grade school year, we had our final “bee” and I won. I went on to a contest in Cambridge and competed with all the local winners in the other county schools. won second place behind Frances (later Mrs. Harry Keenan) of Madison, who got first place. My “second place” won $2.50 for our Taylors Island one-room school. I use to wonder how two children from one-room schools could win over all those from graded schools. “Looking back at my quiet, unexciting early life on the Island, with its three schools for white children and one school for colored children, I now realize how fortunate the children were in not having so many diversions and so much interference. Some of the children that attended the Taylors Island one-room schools, and the consolidated school built in 1915, went on to get college degrees, finding that the foundation of knowledge gained at the one-room schools, supplemented by their parents’ insistence on doing the right things, was adequate and good.

John S. “Pat” Neild

April 2, 2001

As I get older, it becomes apparent to me that I grew up in a time and place that only a few living today remember. My grandchildren have no knowledge of life without paved roads, television, refrigerators with freezers, a school bus that comes right to your door, electricity, cell phones, and on and on. I considered writing about my experiences growing up on Taylors Island. But I recently came across some letters that my Aunt Hester A. Neild wrote to my mother, Mabel Neild in the 1960’s.

Some of you will remember my “Aunt Hester”. She was teacher and principal at East Cambridge School for more than 50 years, finally retiring only because she had to at the age of seventy. She loved to read, tend her flower garden, and write letters. She was born in 1902 and lived on the Island directly across from the general store. Some of her letters are real history lessons. Those about Taylors Island are treasures to be enjoyed, and that is why I offer them for your enjoyment. These are her words.

“Sometimes my thoughts go back to the early days at Taylors Island, and in my mind I can still look across the road from my house and see the old Chapel of Ease, and horses lined up there for shoeing, and I may walk on past the Chapel to the Slaughter Creek shore to the small wooden building where old Charlie Balderston – a genial Negro – sold a quart of shucked oysters for about $.15. I remember the Old Chapel being used, at other times, for Church Suppers, Strawberry Festivals, or Socials for the Island churches. Now it has been restored and moved to the grounds of the Grace Episcopal Church, where I was organist for 15 years during my early days of teaching. When the Old Chapel was used as a blacksmith shop, Mr. Bill Dashiell kept the forge hot and ready for shoeing the horses, and for repairing the iron accessories for boats and farm implements.

“Another memory so clear is that of the sprawling old tomato cannery not far from Slaughter Creek. In the summer and fall, there was always a tangy smell in the air from the cooking tomatoes, and there were long lines of trucks and horse-drawn wagons loaded with tomatoes, waiting to be unloaded. They were unloaded for weighing, scalding, skinning, canning, labeling, and then the filled cans were loaded for hauling away on the Old Emma Giles steamboat, which came to the Island twice each week. Later, after the new “State Road” was built to the Island, hauling was by truck. From our house, we could hear the talking and singing of the Colored workers above the clatter and hissing of the machinery and the steam used for scalding. It was quite an adventure to walk through that busy hive of industry, and be warned “don’t come too near the hot furnace, or belts driving the machinery, or the conveyors carrying the buckets of tomatoes and cans”. It does not seem possible that all this has vanished and exists only in our memories.

“Close to the cannery and on the same side of the road, I recall that there was a long, gray, wooden country store. It bordered on the Island’s oyster shell road. If one approached the store from the cannery, the rear of the store was reached first. You might walk over the “stile” (up two steps – over – down two steps) and reach the path leading to the front porch of the store. Or, if you wanted to walk further and go past the broad back of the store to the big gate used by the wagons, one could then go into the side door of the giant warehouse called the “grocery”, or onto the front porch of the store. This path took you by a narrow building that was a “carpenter shop”, used by the local undertaker, Mr. Henry Lambdin, to build and store coffins. It was fun to go through the gloomy interior of the “grocery”, so full of all kinds of things for the store. Then into the fascinatingly cluttered “store” with its long, long counters, its bins of flour, chicken feed, hog feed, horse feed, etc., and the gleaming glass showcase with its assortment of penny candy. There were horehound drops, stick candy encircled with gaudy rings, little tin pans of white candy with a blob of yellow to make it appear like a “fried egg”, and rainbow coconut ribbons. It is nice to recall the chocolate “Penny Pigs” that sometimes had a real penny inside. For the sake of finding that hidden penny, we sometimes spent several pennies. And I like to remember the Prize Boxes for a nickel, and the glass showcases of ribbons, and the counters loaded with bolts of cloth to be bought by the yard, or half-yard, and the horse blankets, and horse collars, and harness, and stationary. Then there were barrels of peanuts in the shell, a showcase with cigars, pipe tobacco, and chewing tobacco. It always seemed the people who bought the old “plug tobacco” were getting a special treat. There were oblong blocks of the brown “delicacy” and the men would get a generous slice for a nickel, then quickly begin chewing it with delight. It really was a wonderful place, and I know we were all sad in 1916 when that old store was destroyed by fire.

“It was sometime around 1916 or 1917 as I was going to school on the Island, and it seems to me that Mr. A. L. Stevenson was the teacher. I remember that we all left the school grounds and hurried down toward the “big blaze”, with our teacher cautioning us not to go too close. It seems they were experimenting in the store with “gasoline lights” in hopes that they could replace the old “coal oil” lamps.

“When using my shiny new refrigerator that makes ice cubes with such little effort, I often think of the “dairy houses” on stilts that were in every yard on the Island. Inside the cool little enclosures, there could be found a delicious homemade pie or cake, or “hogshead cheese”, or cornstarch pudding, or eggs laid by the family’s hens. The folks on the Island all had their own cows and plenty of milk. Plainly, in my mind’s eye, I see the cheesecloth bags of “clabbered milk” hung on nails or hooks and draining beside the little house to make “smearcase”. The making of “smearcase”, now known as cottage cheese, was an everyday chore and an easy one. We ate the delicious “smearcase” covered with sugar, or molasses, or preserves, or just plain. No canned fruit has ever tasted as wonderful to me as the peaches, pears, cherries and apples it was just customary to prepare and “can” in those days. Never have I been fortunate enough to find or make a “molasses” pie as good as my mother made with black molasses bought from a barrel at the country store and topped with slices of lemon.

“By fishing, crabbing, oystering, farming, building, and processing, the people of the Island were always sturdily self-sufficient in those days before the “State Road” was built in 1916. It took a long time to go to Cambridge over the old oyster shell roads. I remember how, when my father served on the jury, he often stayed overnight with his sister’s family at Church Creek rather than drive the long miles through the dark “big woods” and over the desolate road from Madison to the Island after dark. That sister was Mrs. William Willis. If my father planned to return home that night, I sometimes went with him as far as Church Creek, and stayed to play all day with my cousin Eleanor. As a child I thought “How I will enjoy driving a horse when I grow up!” But at 16, I had an automobile operator’s license and could drive the car my father had bought when the new road was built to the Island. We mainly used the car for the 16-mile trip to Cambridge, and no longer had to use the horses and carriage for that trip. I never derived the pleasure from driving a car that I anticipated I would have had driving our horses “George”, “Maude”, and “Bess”. The barn where the horses stayed was a place of pleasure. It held the horses and cows, wagon, carriages, the surrey, corn and hay.

“Then there were the pig pens we had for raising hogs to be slaughtered for food in the fall. Meat was processed into hams, spareribs, lard, sausage, liver pudding, and scrapple. The fat was cut into small cubes and cooked to make the lard and “cracklings”. Corn bread made with cracklings was a delicacy. Of all the things I loved about Island life, I wanted nothing to do with the killing of the hogs. The squealing of the doomed “sources of food” was nerve-wracking, and my mother would suggest that I “go play the organ as loud as you can to drown out the horrible noise”. “Slaughter Creek” is the body of water that separates Taylors Island from the mainland. My mother use to tell me it was named that because folks drove their beef cattle to the creek to slaughter them. The outgoing tides would then take away most of the unwanted results of the slaughter.

“I remember other diversions we had on the Island. I doubt that present day children get any more satisfaction from their many modern recreations than we did from setting our rabbit traps (called rabbit gums, in those days), and going through the thickets of blackberry and huckleberry bushes, and through close growing cedar and pine trees to see if our trap was “sprung”. It was exciting, and there was a sense of satisfaction when my brother (J. Stapleforte Neild) said, “We’ve caught one!” I suppose I have never admired the courage of anyone more than his courage when he raised the trap door and, somehow, managed to grasp that squirming rabbit by its hind feet. Then we would go back through the woods and up the lane to the house to receive the praise of our mother. We knew the rabbit would be a delicious supper the next day.

“Besides catching rabbits, the neighborhood children would fish, crab, find turtles and watercress, gather eggs, and many other fun things, and those things gave us a sense of adequacy and satisfaction. The fact that our parents were always home in the evenings to help with our homework and direct activities gave us a feeling of security that was real and deep. There was never a need for a psychologist or psychiatrist that I can recall. And we did not suffer poor education. I remember how my mother drilled me in the “multiplication tables” and in “spelling”. We were never exposed to “phonetics” during our entire school life, and yet, spelling and reading seemed very easy. We had “spelling bees” in school every day and got to be good spellers. At the end of my fifth grade school year, we had our final “bee” and I won. I went on to a contest in Cambridge and competed with all the local winners in the other county schools. won second place behind Frances (later Mrs. Harry Keenan) of Madison, who got first place. My “second place” won $2.50 for our Taylors Island one-room school. I use to wonder how two children from one-room schools could win over all those from graded schools. “Looking back at my quiet, unexciting early life on the Island, with its three schools for white children and one school for colored children, I now realize how fortunate the children were in not having so many diversions and so much interference. Some of the children that attended the Taylors Island one-room schools, and the consolidated school built in 1915, went on to get college degrees, finding that the foundation of knowledge gained at the one-room schools, supplemented by their parents’ insistence on doing the right things, was adequate and good.

John S. “Pat” Neild

April 2, 2001

The above photo appears in the book Steamboats Out Of Baltimore by Robert Burgess and H. Graham Wood. The book is available for review in the Maryland Room of the Talbot County Library.